The 74th Berlinale, just like a year ago, gave the major prize to a documentary: the jury chaired for the first time by a woman of African descent, actor director and producer Lupita Nyong’o, awarded the Golden Bear to female French-Senegalese director Mati Diop for Dahomey. Just a coincidence, because the award to a work that wisely reflects on the legacy of colonialism is well deserved. Halfway between fairy tale and public debate, the film’s main topic is the return to Benin (a West African country) of 26 pieces of art stolen from France during the colonial era. One of the statues tells its return journey in first person, with a voice coming straight from the dark recesses of the past to reaffirm its identity and welcome its old/new home. The second part is more focused on the debates involving youngsters from Benin, who gathered after the return of the Beninese artifacts in order to discuss the recovery of local tradition in relation to what colonialism stole and not necessarily gave back; for example the language, because the debates are held in French. Diop gives voice to both the statues’ past and the youth’s present in an impossible yet fruitful dialogue, and thus shapes an exchange of views between the artistic representation of an ancient people, and the political representation of a contemporary youth who questions their own culture.

Two English-speaking actors also took the stage at the Berlinale Palast to collect Silver Bears for best supporting and leading performance. Emily Watson got the prize for the small but intense role of a nun, symbol of one of the saddest pages of Irish Catholicism, in Small Things Like These: precisely in the scene in which she face the protagonist, expressing a cruel indifference while keeping a friendly and smiling attitude, she pushes him into action to finally help people around him. Sebastian Stan, awarded for A Different Man, decided to thank director Aaron Schimberg and co-star Adam Paerson for trusting him and his interpretation of disability, first experienced from the inside and then observed from the outside.

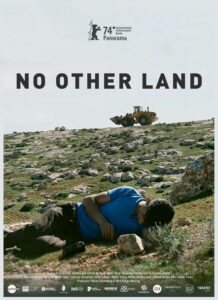

No Other Land poster (2024)

A different jury awarded the Berlinale Documentary Award to No Other Land, directed by a collective of two Palestinians and two Israelis filmmakers, that was also one of the most anticipated films at an event marked by constant allusions of the ongoing conflict in the Gaza Strip. This film, however, was shot in Masafer Yatta, in the southern West Bank: combining the internal and external viewpoints of the Palestinians citizens and the Israeli activists, it witnesses the actions of the Israeli army to drive out Palestinian residents from their lands, with the excuse of creating a military training area. We can clearly notice the injustice of these actions, the unnecessary cruelty of the Israeli soldiers, the pain of the children who watch the destruction of their schools and playgrounds; and yet during the film the question about what actual contribution cinema can give to change things is raised. If the goal was to raise public awareness and perhaps influence the policies of the Israeli government, the result is unlikely to be achieved; indeed, arguments have been tense in Berlin. The Q&A with the audience at the end of the first screening was lively: the Palestinian director Basel Adra said he strongly disagreed with the Berlinale Statement on the crises in the Middle East (and elsewhere), immediately afterwards agitated choruses in favor of Palestine were heard coming from the audience, then someone else from the audience recalled in response the crimes of Hamas and that a shared political solution was necessary, but while speaking fought with the youngsters chanting those choruses. During the Berlinale Awards Ceremony, jurors and other prize winners called for an immediate ceasefire in the Gaza Strip; in the next days, some high-profile German politicians objected to the one-sided point of view and the risk of antisemitism in some of the speeches (a very sensitive topic in Germany), which are strong objections because the festival is supported by public funds too. Therefore, unfortunately we did not get from this year’s Berlinale an articulate and balanced reflection on such a sensitive issue as the question of Palestine, but only further divisions.

Such strong participation of local public opinion is a reminder of how accustomed Germany is to analyse the tragedies of its past and director Julia von Heinz, in her first English-language film Treasure, indirectly addressed the worst of them all. In 1991, a New Yorker woman and her Polish-born father (Lena Dunham and Stephen Fry) take a trip to Poland so that she can see for the first time where her family came from. It starts as a comedy (she doesn’t speak Polish and her over-protective father behaves exuberantly) but the further along the journey they go, the deeper they get into the painful memories of the man, a Shoah survivor. What works best is the chemistry between the two protagonists in portraying a tortuous father-daughter relationship that lead them to drift apart over generational and cultural differences and then to reconcile over an affection consolidated by the rediscovery of their origins.

From Hilde with Love (Andrea Dresen, 2024)

It is more difficult, at first, to figure out what the historical period of Andreas Dresen’s From Hilde, with Love is: the 1940s at the height of the Nazi era, albeit without the classic iconography of the period. After the arrest of Hilde, a pregnant young woman, half the movie goes on to tell the story of her imprisonment, alternating with the other half going backwards in reverse to her most distant memory. She is one of the young activists inside the resistance movement, but the details of their ideologies are not revealed: the characters are not glorified (Hilde really existed and former East Germany considered her a heroine), instead they are put in contact with today’s youth, capable of political engagement and at the same time eager to live their youth to the fullest, have fun, love. Without succumbing, at least in the will to continue dreaming, even to the Nazi ferocity that tolerated no dissent.